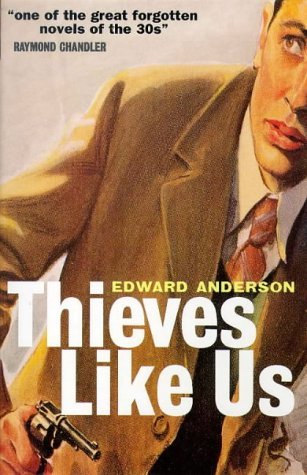

Title: Thieves Like Us

Rating: 4 Stars

Over the past couple of years, I’ve gotten pretty deep into noir novels. By now, I’ve moved past the giants of noir like Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. I have a soft spot for David Goodis, in some ways the most noir of noir authors. In addition to them, I’ve sampled Cornell Woolrich, James M Cain, Jim Thompson, Chester B Himes, and Patricia Highsmith, among many others.

I checked out a collection of crime noir novels from the local library. In that collection was an author that I’d never heard of. Edward Anderson wrote a novel called Thieves Like Us.

Never having heard of him, I did some research, and it turns out that Anderson led an interesting life. First of all, he only published two novels. Thieves Like Us was his second. Born in 1905, he wrote his two novels in the 1930s. Before that, he was a printer’s apprentice. He got into the newspaper trade. He worked as a reporter and a copy editor. Working at some ten different newspapers in his early career, he thought of the newspaper business as legalized prostitution.

Inspired by the Lost Generation and the expat writers like Hemingway, thinking that Paris was the place to be, he quit the newspaper game and moved to France. Realizing that he was too late and that everyone had left, he moved back to the states in the midst of the Great Depression. For two years, he rode the freights, slept in parks, and asked for handouts. Introduced to the son of a preacher that had a large library, he became inspired by what he read and decided to become a writer and write about living life as a hobo. Gradually he began to write short stories for detective pulp magazines.

After he published his two novels, Hollywood came knocking. Although he was able to make some money in Hollywood, none of his film treatments ever made to the silver screen. Disillusioned by Hollywood, he became an alcoholic, eventually suffering from DT’s. He ended up in AA recovery. He died in 1969 in obscurity with only the two novels to his name. Two film versions of Thieves Like Us were made, including one by, of all people, Robert Altman. I guess that I shouldn’t be too surprised since Altman made the noir (and actually surprisingly good) The Long Goodbye the previous year. Anderson received a grand total of 500 dollars for the film rights.

So, given all of that, how is Thieves Like Us? Well, it turns out, pretty darn good.

The protagonist is Bowie. Along with his older, more experienced friends Chicamaw and T-Dub, they escape from prison. Needing cash, they take to robbing banks. T-Dub, having robbed already robbed close to thirty banks, is the leader. Bowie is just looking to make a couple of thousand dollars to set himself up with a stake.

Initially, they are successful. They rob a couple of banks and each end up over ten thousand dollars. Chicamaw is wild and blows through his cash. Bowie, believing in loyalty to friends, lends him additional money.

Bowie meets up with a young woman named Keechie. On the one hand, he’s in love with Keechie and wants to start a new life with her without crime. On the other hand, he just can’t stand the thought of betraying his friendship with Chicamaw and T-Dub. When he meets up with them at one of their prearranged rendezvous, Chicamaw has once again blown through his stash and T-Dub is eager to rob another bank. The divided loyalties of his love for Keechie and the bonds of his friendship of thieves is the fulcrum of the novel. Being a noir, you can guess that this will not end well for anyone.

I found two things interesting about this novel that sets it apart from other noir. One is the political point of view. Usually in a noir novel, the politics, if present, are pretty subtle. Here it is front and center. In fact, it drives the title of the novel. In several instances, one of the thieves compares themselves to prominent members of society like police, bankers, and lawyers and declares that these professions are also, in their way, thieves. There’s a famous trial scene in The Wire where the infamous robber of drug dealers, Omar Little, on the stand, makes the point that the defense lawyer is just as much a part of the ‘game’ as he is. One has a shotgun while the other has a briefcase but they are both players in this game.

Towards the end of the novel, one of the lawyers that is in sympathy for Bowie has a fairly extensive monologue on the state of capitalism in American in the 1930s. It’s a bit reminiscent of the final section in Sinclair’s Jungle, where a character goes on a multipage rant about the forces that drive capitalism.

There’s a form of literature that came of age around this time called Proletarian Fiction. It was fiction written by and for working class laborers (Anderson certainly fit that bill). I’d never heard of this genre before. Thieves Like Us certainly would seem to fall into that category.

The second interesting observation about this novel is its verisimilitude. Apparently, in writing about Bowie and Keechie, Anderson was inspired by Bonnie and Clyde. In his various reporting jobs, Anderson spent time visiting prisons getting to know inmates.

As I was reading the novel, I found myself thinking about Bryan Burroughs history of crime figures in the 1930s. Called Public Enemies, it’s a historical recounting of crime figures like John Dillinger, Alvin Karpis, Baby Face Nelson, Pretty Boy Floyd, and Bonnie and Clyde. You’d expect that most of the Burroughs’ book would be about the dastardly deeds of all of these criminals. In fact, they all spent relatively little time doing crime and spent most of their time in hideouts or getting flushed from hideouts and having to find another hideout.

You see the same thing in Thieves Like Us. Very little time is spent on the bank robberies. Most of the time, the robbers are on the lam, either together or separately. They’re constantly having to look over their shoulders and, at the first sign of trouble, are ready to pack up and flee.

In fact, reading Thieves Like Us seemed almost like a fictionalized version of the lives of a couple real life bank robbers.

Having that level of reality raised it above the normal noir fare.