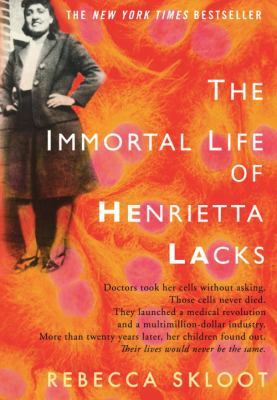

Title: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

Rating: 3 Stars

This is the story of Henrietta Lacks. Suffice to say she did not have an easy life. Born Black in Virginia, her mother died giving birth to her tenth child when Henrietta was four. Staying with her maternal grandfather, a poor tobacco farmer, she shared a room with her cousin. Pregnant by that cousin, she gave birth at fourteen. Later marrying the cousin, she ended up giving birth to five children, including one with development disabilities. Shortly after giving birth to her last child, she was diagnosed with cervical cancer. She was treated for it at a segregated hospital but ultimately died a painful death at the age of 31. Her story might have ended there as just another story in a innumerable series of poverty and racism in the Jim Crow South.

The segregated hospital that she was being treated at was Johns Hopkins. There were researchers there that were trying to figure out how to keep cell cultures alive. Previously these cultures had only survived a day or two. As the doctor was treating Lacks, he took a culture of her cervical cancer cells and sent them to a researcher. Fully expecting them to die like all of the others, he was astonished that not only did the cells survive but they flourished and multiplied, seemingly with no end in sight. The cells were effectively immortal.

This had enormous consequences. First of all, this was in the 1950s during the desperate search for a polio cure. Jonas Salk had a possible vaccine but estimated that they’d need to experiment on two million monkeys to validate its safety and effectiveness, thus making it prohibitively expensive. Being able to perform these tests on thriving cell cultures was a leap in technology. To accommodate these new exciting developments, factories were created to culture and grow these cells (now known as HeLa). They proved to be so robust that quite literally trillions of cells were grown. Everyone was using them in their biological research. It was estimated that if all cells were laid end to end that they would encompass the planet several times over. HeLa cells were used in everything from cancer research to nuclear energy to space programs. Over ten thousand patents refer to them. They were the workhouse of biological research.

They were so robust that they caused industry problems. Traces of her cells were found in contaminated samples. In one particularly disturbing study, ten samples from different animals were collected under extremely rigorous conditions and yet some eight of them proved to have DNA markers of a black woman. This contamination caused millions of dollars of damage and brought several studies into question.

While all of these exciting developments were happening in the biological research world, the Lacks’ family continued on obliviously. They had no idea that her mother’s or grandmother’s cells were being used. In fact, Henrietta Lacks was never asked and she never consented to the use of her cells. Although not allowed today, that was considered standard practice in the 1950s. The Lacks family continued to live in poverty. All of Lacks’ children had an assortment of health problems (cousins really shouldn’t marry). One of her children was horribly abused after her death by the woman raising him. He ended up with severe anger issues that played a part in the murder that he ultimately committed. Several other descendants also ended up performing criminal acts and/or landing in jail. Lacks’ developmentally disabled child ended up at a segregated institution. It seems clear that several painful and dangerous brain experiments were performed on her (including one where all of the fluid is drained from her brain to allow a clear scan). Tragically she died at fifteen.

The book follows those parallel paths. At the same time that you read all about these scientific breakthroughs, you read of the Lacks’ family struggles. Until the contamination issue arose and researchers needed blood samples from surviving relatives for DNA comparison, no one gave any thought at all to the family. Billions of dollars in profits were made while the Lacks lived in grinding poverty and poor health.

The author developed an emotional bond with the family and did help bring about a measure of acknowledgment if not closure from the scientific community to the Lacks’ family. Some of the current generation have gone on to higher education with the goal of understanding and furthering the legacy of their ancestor.

Regarding the three star rating, I found that the scientific part to not have answered a couple of crucial questions. It did explain why the cells were immortal. Normal cells have a counter that decrements as it multiplies. Once it reaches the end, the cell dies. Cancer cells essentially reset the counter so they never die. Even so, one thing that is not clear is what makes Lacks’ cells especially robust in comparison to other cancer cells. Secondly, if they were worried about being so reliant upon one cell culture, why not just harvest cells from other cancer victims? It’s still not clear to me exactly why Lacks’ cells were particularly unique.

This might be just a personal preference, but I was a bit discomfited by the voyeuristic nature of the Lacks’ family part of the book. There was a much too intimate description of one of the Lacks’ relatives having a very personal spiritual experience with Henrietta’s daughter, Deborah. I also found the, again very personal, descriptions of Deborah’s physical and, more importantly, emotional problems to be intrusively voyeuristic. I’m sure that she gave consent but she is pretty clearly not exactly stable. When you consider that the author was a young white woman, it just seems somehow exploitative in of itself.